Nick Schutzenhofer: Egg Contempera

Archived series ("Inactive feed" status)

When?

This feed was archived on October 30, 2022 11:52 (

Why? Inactive feed status. Our servers were unable to retrieve a valid podcast feed for a sustained period.

What now? You might be able to find a more up-to-date version using the search function. This series will no longer be checked for updates. If you believe this to be in error, please check if the publisher's feed link below is valid and contact support to request the feed be restored or if you have any other concerns about this.

Manage episode 184677519 series 1523403

By Debbi Kenote and Til Will

Full audio interview: https://openhouseblognyc.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/nickshutzenhofer_oh_fin.mp3

Led down an industrial alley in South Slope, BK, in the noisy shadow of the Gowanus Expressway, we found ourselves at the door to Nick Schutzenhofer‘s studio. Sickeningly sweet air wafted down the hall from the neighboring Shaheen candy distribution. We were surprised to discover the most immense painting practice we have seen in NY to date, and a distinctive surface quality developed using the ancient medium of egg tempera.

DEBBI KENOTE: I’m a little overwhelmed by how many good paintings there are around me.

NICK SCHUTZENHOFER: That’s sweet of you.

TIL WILL: I guess we’ll start by saying we are here in South Slope, in Nick Schutzenhofer’s studio and we’ve got a nice assortment of new paintings in front of us.

DK: Who are we?

TW: I’m Til.

DK: And I’m Debbi.

TW: And Nick’s here.

NS: I’m here.

TW: He’s here.

DK: We are going through the lens of Open House

TW: Yes, so, I like to start by finding out a little bit about how you got into art making, where you grew up, when you started.

NS: Yea, let’s see. I was born in Missouri, in a small town called St. Joseph, who’s really only reason that it might be well known is that it was the start of the Pony Express, and it was also where Jesse James was killed, that famous cowboy. I lived there until I was about 5 and it was really rural. And then my family moved to a western suburb of Chicago, called Naperville, which is about 40 minutes outside the city. And basically as a little kid, I was either outside, building forts and going fishing, or I was at my desk making these tiny little intricate drawings of airplane fights and battleships and…

TW: That’s amazing.

DK: That sounds like an ideal childhood.

TW: The first drawings I made were airplane battle scenes.

NS: Yea, they’re really good. My mom gave them all to me recently, and they’re strangely like…the space in them is really topographical almost, things are flying at you but the action is taking place across the flat surface. They’re really weird.

TW: I’d like to see those some time. I know that I have some of those drawings somewhere in a box and I’m curious to see how they compare to the ones you did.

DK: Do you think you think about those childhood drawings while you’re making these, ever?

NS: Um, maybe in some way. I mean a lot of my work is still on paper, right? It’s still lots of small mark making and there’s this sensation of things being like a kind of all over composition and sort of flat, but at the same time this indication of deep space. And I think a lot of things I did in those childhood drawings have that similar quality where they feel like a topographical map in the way that a map would be laid flat and viewed from above. A lot of that came from how I was working on them because I was hunched over them at a desk. But they had this space as well that you could go into. So yea, I don’t think about those drawings in particular, but I think a lot of the things I think about, in terms of how a picture is structured, might still apply in some ways. But I was making tons of drawings as a kid, you know my mom, she painted for some time when she was younger, and would always take me to the Art Institute in Chicago, and I remember having really profound experiences there as a child. My favorite area of the whole museum, and what got me kind of into even the idea of going to a museum, which seems like a really stale place for me as a kid. There was this hall of arms and armor in the Art Institute, which is a long hallway that is now filled with Indian Art from Southeast Asia and it’s these Ganesha sculptures and stuff like that, but back in the day it was swords and knight’s armor and all this crazy, you know, sort of little boy stuff. So me making these kind of violent battle drawings, I was super into going there and seeing that stuff, and then by proximity you happen to wander into these other galleries in the museum, and see paintings. I was always really into this Giovanni di Paolo painting of the beheading of Saint John…

DK: That’s a great painting.

NS: Right? You know that one, it’s in three panels?

DK: Yea.

NS: It’s super violent, like there’s this crazy blood spraying out of his guy’s neck hole after he gets his head cut off…

DK: It’s a great painting.

NS: And I remember seeing that and being super into it, and fast forward many many years, I took a bunch of art classes in high school, got to go to the contemporary art museum and see Cindy Sherman and got really into photography and ended up studying art history in college and minoring in photography. My first works that I was making were photo based, outside of the drawings that I kept making. I’ve always had a drawing practice and kept a sketchbook and made just drawings of stuff. And so, yea, I was really into photography and I remember my show culminating my undergrad experience, I made these….I was taking these photos out of books of paintings I really liked and then I would collage them together in the dark room and make an 8 x 10 image that would be like a combination of Francis Bacon and Titian, or something like that. Weird, and from different times and different…

TW: Remix.

NS: Remix! Totally, totally. Just mixing it up and making my own kinds of compositions. And then I would scan those, I would high res scan those and buy these really nice, it was called a lando print or something like that, and they were these really nice high resolution prints and I would print them off semi large for a photo. And those were really the first works I was making. And kind of like thinking about Sherrie Levine, was my favorite artist at the time and her photo appropriations and how she was photographing a photograph. And I think that’s still something I think about a lot, and I still love her work. Well yea, that’s how I got started. Just like any person who has an inclination to make drawings and does it compulsively and then gets interested in other areas of what an artist does.

DK: So do you consider yourself a painter?

NS: That’s a good question. I guess I do now, maybe. Yea, sure, yea I don’t not consider myself a painter. I consider myself a…yeah I guess painter would be the easiest way to say it. I think more about images than I do necessarily about paintings, but I think painting is the way that I get there now.

TW: I wanted to ask you, transitioning out of that question, how did you get into egg tempera? It sounds like you started with this photo collage thing, so how did you transition into making paintings?

DK: And can you walk us through the process a little bit, how it all works?

NS: Sure. Yea, I was making drawings on paper in just ink for many many years, and I had a show at this artist run space in Chicago and I made these really large scale really like, there’s a lot of small mark making in them, these big drawings. And I don’t know, I guess I made a bunch of work in that vain, of just drawing, because I lost the facilities of having the photo dark room in college, right, so I was looking for a way to work with the same ideas I had been working with. So I was like fuck it, instead of just taking pictures of this stuff and using a dark room I can just draw it, right, and it’ll be the same, sort of, and maybe even a little bit better. So I started making drawings, appropriating imagery from various sources and combining it together. I made this whole series of work and it was really labor intensive and I applied to graduate school with it, and didn’t get into the school I wanted to go to. So I felt like I kind of had to change my work, and I thought since I was applying to a painting department maybe I need to start making paintings. I had never taken a painting class, so I started just slowly accumulating with the materials, and I bought this materials and methods book by Ralph Mayer, right, you guys know, it’s this sort of classic text book. There’s a whole chapter in there on egg tempera and there’s a chapter on oil painting and all of the mediums and stuff like that. And I started actually with oil paint and I got frustrated so fast because I’m kind of impatient. One of the things I loved about drawing, like drawings just in ink of paper, was the speed that you could work. You could make a mark or a bunch of marks and it dries in like 10 minutes. Oil painting is so much slower. So I experimented with oil painting, applied to grad school another time, didn’t get in again, and finally, I was still making paintings, and still sort-of trouble shooting, finally I get into the school I wanted to go to, and I took this materials class at the Art Institute in Chicago, and they teach you how to actually use the mediums and stuff like that. But one of the things they show you is how to paint with gouache and distemper and what’s that fucking milk paint called…

DK: It’s called milk paint, but there might be a fancier name.

NS: Yea I can never remember the fancier name. But they also showed us egg tempera, and there was something about it that I really liked. I think it was the transparency of the paint that you could get and also the speed at which it dries. You can make a mark and it’s literally drying as you make the mark.

TW: Oh, wow.

NS: So you can work really quickly, and I like that feeling, and I like the way that it looks, you can make it look like marker. It feels almost backlit whenever you paint with it on a really bright white surface and I like that kind of, the light that it has, or the way that it holds light is really interesting. And you can make it so transparent because it’s water based essentially, that it feels backlit, like marker, it’s super transparent and kind of lovely. It’s bright. It had this speed, so yea I guess my first experiences with it were in a classroom as a graduate student. I kind of put in on the back burner for a year, and then reallys started working with it in a serious way in my second year of graduate school. I was making really really minimal, different work than what we’re looking at right now. I got super frustrated with that way of working. It’s kind of funny I was making these big paintings that were just big pieces of paper glued onto canvas. And that would be it, just white paper glued onto canvas, and it was like there was nothing. And I got sick of actually having to justify my decisions to not have anything there. This sort of hollow, like I needed to have this really intellectual discussion about why I didn’t have anything on the surface. Why was it just a surface, why was it totally empty? And I got kind of frustrated, I feel like maybe I was just a little self conscious, I guess maybe I wanted to make the kind of work I’m making now, but in an academic setting it felt, I felt like I didn’t have permission or something like that. I felt like I had to make this slick-looking, empty minimalist work and then it was basically out of frustration, I started making these super bright colorful egg tempera paintings, in my second year. It felt really good and I didn’t give a shit what people thought about them. I just like this feels right. Yea.

TW: That brings up an interesting question. Do you think that the grad school setting brings out this kind of challenge to feel like you need to fit what’s going on?

NS: Sure, I mean I think a lot of it was I trying to make my work look like what I was seeing on Contemporary Art Daily or something like that. And feeling like I wanted to have an aesthetic that could be viable or something like that. I felt like I was trying to make something that could fit into a gallery at that moment, you know, instead of thinking about what I actually had a desire to make and what would make me happy, as a painter.

DK: How did you come upon the imagery you use now? It looks like there’s some serpents, maybe forests, people…

NS: Oh yea. A lot of it is still appropriated from other sources, I’ve been working since about 2014, I’ve been using this printmaker, Alfred Kubin, you know his stuff?

TW: Yea, you told me about him recently.

NS: I’ve been using his stuff as source material for the past three years maybe. He wrote this novel called The Other Side, and he illustrated it as well. He wrote it in 1913, and it’s this sort of dystopian examination of the rise of fascism more or less…

DK: It’s definitely relevant at the moment.

NS: Totally. Totally. I was even thinking about that back then, this was 2014 so Obama was still president and we were in a good situation politically…

DK: Better situation politically.

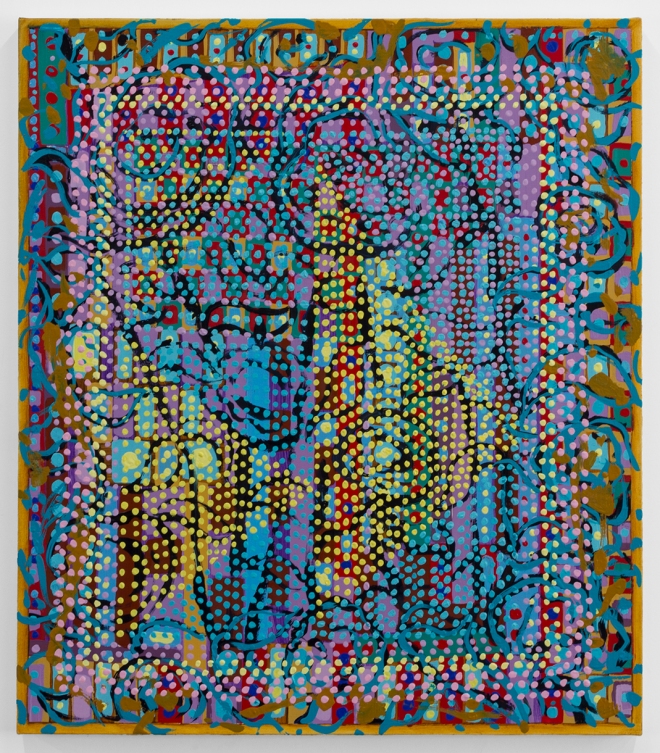

NS: Better situation politically. But yea, I’ve used a lot of his stuff in my work and a lot of Kubin’s work. I think a lot of the more seemingly tangential, what feels like abstraction, is still related directly to his work and sort of work of that time period as well. I feel like some of them are so direct, like the painting right there, in the middle, is a very direct appropriation of imagery from this piece he did called The Descending Line, which is a family portrait essentially of him being the one sort of at the bottom of that stack of beings, and this snake figure is his dad and the woman is obviously his mother.

DK: How would you describe this painting, Til?

TW: Well it’s purple, it’s pretty purple. Looks like a purple underpainting, yea basically the way Nick described it, is kind of what we’ve got, but it’s sort of framed as if this image he is describing is framed with some sort of wavy frame. But yea I’m interested to hear more. Egg tempera feels like this sort of traditional medium that I would associate more with realist painting.

DK: Spiritual, religion…

TW: Yea, Sacred painting of like the 1600s or something. Do you think about the historical context of egg tempera as a medium when you’re approaching painting?

NS: Sure, yea totally. I guess all painting for me is either spiritual or it’s ironic, I mean right? So I would definitely put mine in the camp more of spiritual than irony. I never really thought about irony as a sustainable way of making work, I mean it feels so disingenuous or something like that. But I’m not a very spiritual person and I’m not religious, but I like the, if you take illuminated manuscripts for example, the way that a lot of the space is structured in the images in those is pretty crazy, and the kind of invention people used when making that kind of work is pretty phenomenal, and I guess I come to art making as more of a person who’s interested in history and a viewer. I mean I studied art history as an undergrad, it’s still something, maybe a kind of a parallel to my work is this sort of research I do, visual research, or, I wouldn’t use the word scholarly, but reading that I do about history or other artists and things like that. I mean I like the kind of weight that it has I guess, as a medium in that it has this connection to this really old way of making images, but I mean for me it was super practical also. It dries really really fast, you can work fast. I got this sort of kick out of how you can manipulate color and layer these sort of transparencies and it’s just sort of beautiful and has a different feeling than most other kinds of paint. And also, if you google egg tempera painting, you get the worst kind of craft project bullshit, you know, it sort of has this crafty like, it’s not a very elevated thing unless you’re looking at it in this sort of really historical context. Contemporary society, nobody really uses it. It’s sort of this un-utilized medium, but it’s so easy and you can get this shit down at the deli. You can go there and can buy eggs.

DK: So do you have eggs in your fridge at the moment?

NS: I do have eggs, yes.

DK: And how do your paintings smell?

NS: They smell a little eggy sometimes, especially the larger work, but uh, I address that. I have this lavender oil that I spray on the back of them, so it has a fragrance too…

TW: Wow. So there’s a trick for eliminating the egg odor?

NS: Well the egg odor is only while it’s curing too. The painting, like this, it might take 6 months for it to cure fully, but you’re not going to have much of an egg smell after a week or two. It’s not so bad. I remember I was in LA last year, and it’s a lot hotter there obviously, and I had AC in my studio but I was making several large paintings at once and all on the floor. And I remember walking in there sometimes and it smelling like sulphur or something, it could really gag you…

TW: Well I think that’s really a radical thing that you’re doing and I was really surprised when you first told me that you work in egg tempera. Because I was like, I don’t know anybody who does that. Especially this scale. So that got me really interested. I want to shift gears a little bit to some of your most recent work, and maybe ask you a little about, it sort of seems to be referencing, or is reminding me of Op Art sort of meets, drawing from Aboriginal paintings of Australia. Do you see, are you thinking about that? Are you feeling like you’re referencing that? Because they definitely vibrate.

DK: They really do.

TW: They have this thing where you look at them and there’s this layering where you get this hot under painted color and then it’s contrasting with this dull color and it really creates this vibration.

NS: Yea. I mean my mom’s from Australia so I’ve looked at a ton of Indigenous art from there, I was just there last summer for about two weeks and just saw these amazing collections of that kind of work. And I’ve always loved that that work is so loose. The mark making is tremendous and it’s very unpretentious in a lot of ways. I don’t think I’m directly referencing any of that stuff. I feel even the work that is more visually what a person might call an abstract painting, I always think of myself as making a picture of an abstract painting and not making an abstract painting per se. Because I’m not really abstracting from a thing, I already have an idea in mind about what the image is going to be. I mean, there’s not really like abstracting that’s happening.

TW: Right.

NS: I Mean I always just think about them as an image of an abstract painting.

DK: That’s interesting.

TW: So this one we’re looking at on the right, it sort of has the longer green lines on top, and it looks like maybe the shorter green lines on top of a hansa yellow, like really bright yellow, that painting, what painting are you making a painting of, or what picture are you making a picture of?

NS: Sure, sure, I guess it’s kind of like a mix of like Daniel Buren and I don’t know who else, maybe Lichtenstein, or something. Yea, I don’t know. I don’t know if it’s necessarily a direct reference in these. Those are really new, I haven’t even really digested those yet. I guess some of these I’ve been trying to think of a way to build a body of work that uses something like more representational like that and that is a direct appropriation, with something that can be more visually abstract and maybe have them support each other, right? I mean the colors are not so far off from one another. The surface is the same. A lot of the marks are the same kinds of marks, the transparency is there. So I’m always trying to think of how I would put together a show. So a lot of what I’ve been thinking about is building a painting show like how a person would build a set for theatre. So you have things that are kind of driving a narrative in some ways, and then you have elements that are not necessarily props, but functioning like a scenic backdrop or you know, sort of as important as a character on the stage, but they might be something that’s sort of structural. So trying to figure out a way to make them work in tandem and have them support each other. I mean another way I think about it is in terms of sound or music, you know you have, I’ve used this example before, but like a barbershop quartet.

DK: I love it.

NS: In order for a barbershop quartet to sound the way it does, you’ve got the dude with the deep ass voice, you’ve got your soprano, and you’ve got everything in between, and they only sound that way when they’re all harmonizing together. And I think about painting that way. How do I make a group of paintings and not a singular painting, that’s supporting an idea across images? Because I think about painting in terms of like how one painting sits next to each other, because no painting is in a vacuum. They’re all kind of like, they’re all with each other. It’s a trajectory of all these people working over all these years and all these different styles, and I think about that. Maybe it’s that the way that I look at work now, and absorb work now, is more in this flattened out way where there’s not like a hierarchy of representation. Yea, where you can have these sort of different elements that go together, even if they’re clashing in some ways, and they can kind of inform each other..

DK: I have a question from that point. We only have time for a couple more questions. It sounds like you definitely have a way of working and you have some imagery and research you’ve been working from for a while. And you have this idea of how you look at a show and a body of work and how they all come together. How do you deal with your day to day experiences of just being a human, and emotions, and does that show up in the work at all? Or is the work more of a retreat from that to kind of go into your own world to escape it?

NS: Oh, yea, that’s a good question. I think it’s a little bit of both. I think there’s definitely things that go into the work that might be more from something going on in my personal life, but then at the same time it’s always been kind of a retreat for me. And sort of zoning out and making something and not, uh, and just being absorbed in the process is super cathartic for me as a person. And I mean I love the solitude of it too, I have a studio mate that I never see, and so I totally value my time in here, just being with my ideas and being with the materials and stuff like that. But you know, it’s hard to keep your own personal life out of your work, I mean you’re making decisions based off your experiences as a person so all of that is going to inflect your choices somehow. And so I think a lot of the choices that I make in my work are definitely coming from these personal places even though it has this sort of, I don’t know, maybe sometimes feeling like there’s an overarching structure. That structure is changing all the time and it’s from just kind of, yea my experiences as a human.

DK: I think that’s a great answer. If Til doesn’t have any burning questions, I love that painting over there, and I heard you say earlier that you love it too. But to me it is a lot different in the sense that…

TW: This is the teal and purple squares that sort of taper into thinner squares in the middle…

DK: It has some language in common with the newest work that you’ve been showing us, which are the lines with the green over the pink and the dots and the bright ones over here. But that one came before these, right?

NS: It did. That was the first painting I made in New York and then…

TW: That’s a hot ticket item.

NS: Haha, yea it is.

DK: Can you tell us about that painting a little bit? I want to hear about it.

NS: It’s funny there’s a painting underneath it if you look at it closely, there’s all these marks underneath that grid structure. It was this painting that’s in the middle here, it was a version of that, because I’ve made several versions of that painting.

DK: And that’s the three tiered family one.

NS: Yea and I painted over it. Because I was like ‘man, I’m in a new place,’ and I just wasn’t happy and thought I should do something different. I felt like I needed to expand a little bit. So I made this painting and it looks like several paintings that I’ve made before. I’m going to paint this grid structure over it and just see what happens.

DK: But it’s like almost not a grid, it’s so wonky…

NS: Yea it’s super wonky, it’s transparent, you can see all the activity behind it, so there’s like a buried image in there. And, you know, I think that actually informed a lot of the other work that I’ve made since I’ve been here, which is the idea of this sort of multi-layered picture that you sort of result in a multi layered picture and maybe there’s buried imagery in stuff. I mean these one’s with the dot matrixes over these kind of colorful grids and stripes and stuff. The lines that you see, the dark lines, they’re like paintings of flowers and shit, yea I guess I was thinking about, how can I do something with these sort of more opaque colors, that is similar to what I do with tempera, which is layering. So it became not about this sort of different way of layering. And in this sort of more, broken up, pixilated way. And I think that painting, the purple and teal grid one, was sort of a stepping stone of getting to the newer work, but it’s something that I’m going to come back to for sure. Just because it was satisfying making it, and it’s satisfying covering up a painting too.

DK: It is. Especially when it’s flat like that and it’s easy.

TW: So this artist that you’re referencing, I can’t remember the name…

NS: Kubin. Alfred Kubin.

TW: Kubin. So right, he came along during the rise of fascism, is what you’re saying?

NS: Yes.

TW: Do you see a relation with that imagery, because what I’m seeing with these dot painting or grid painting, that you’re talking about, over an underpainting, as this sort of idea of a filter of information.

NS: Sure, sure, yea.

TW: And I think that it can relate maybe to the way that we are receiving information.

NS: Totally, And you have to pull through it. You have to look through this scrim to get to something that’s behind this information that’s on top, that isn’t necessarily the whole picture. No I think that’s a good…you’re totally accurate in that kind of read.

TW: Is there a thought with using Kubin, or do you like the way his images read and how, kind of the weirdness of them?

NS: I like the problematic aspects of them. A lot of his imagery is super problematic in so many ways and it was so personal, you know, he was one of these people who had a career as an illustrator for books and he made all of this work that was just for him and you know, he was a fairly respected man in his time as an artist, but his career was pretty much in illustration. Wait, sorry what was the question?

TW: Basically I’m trying to see if there’s sort of a reason for using him specifically for political context and how that relates maybe to the dots that are coming into play, or this filter that you’re creating by layering.

NS: I mean it’s hard for me to say. I started using his work before, I mean I don’t necessarily have an interest in making very politically charged work, I think my impulse comes from a different kind of place. I think it’s kind of happenstance that some of his work and his writing feels more relevant now. But I mean definitely see a connection between the two bodies of work. And I’ve read his book that he wrote, I don’t know, four or five times at this point. There has to be, I still think about his work whenever I’m making these ones with the dots on them. Maybe they’re more like scenery or a setting that he’s in, and not necessarily the more narrative elements of you know, the sort of imagery that he creates to illustrate the scenes in his book. I think of them more as a backdrop or something like that.

TW: Oh interesting, cool.

DK: So I think it’s about time to wrap up, but I want to squeeze in two really short questions.

TW: Do it.

DK: If I can, if I can be greedy. The first one is, the colors, are they just from your peer soul aesthetic of genius, or do they come from a special place, and secondly, how many drawings do you make? Because I know these are drawings mounted, or paper mounted that you paint on, but I see a couple studies over there, does that mix in with how you pick colors too?

NS: Yea, I do a lot of color studies on paper, before or as I’m making a painting. I think the colors themselves…I mean I love purple, right, and it’s because it has such a complex color space, it’s both warm and cool at the same time. Depending on what color you put it next to it can come forward or recede in space. I kind of just love purple, I think it’s a really awkward color. And then some of the other, you know, colors that I choose, I just try and challenge my own taste. I tend to go towards palettes of stuff that I wouldn’t wear, you know? So, like, I never wear purple, ever. You’ll never see me wear anything purple.

DK: I’ve never seen you wear purple, ever.

TW: These paintings are not a reflection of your fashion taste.

NS: No, certainly, and I try and push myself to use colors that are not necessarily conventionally beautiful. I use a lot of this weird rusty red, weird pinks, weird greens, ochres, these kind of earth colors. All of Kubin’s work was black and white, right, so I get to invent a lot of it, and you know, the one’s that are more direct appropriation of his work and related to his writing, I’m inventing a lot of the color palette choices based on the mood of the particular passage that the imagery was taken from.

DK: I like that.

NS: And, luckfully the novel that he wrote, it’s sort of a precursor to a lot of surrealist writing, and it’s very vivid imagery that he describes and you know there’s all sorts of language that uses color within that. And so I’ll use that sometimes. Sometimes it’s just sort of, like I said, coming up with a palette that challenges my taste, but still is visually appealing in some way. But also does things with space, color space, and kind of has this similar atmospheric quality that I dig.

DK: I dig it too.

NS: Ok, cool.

TW: Purple man, it’s the shit.

NS: I love it, isn’t it great?

DK: It’s really great. Well this has been absolutely wonderful.

TW: Thank you.

NS: Thank you for coming by.

TW: Thanks for having us, and yea, you got anything coming up?

NS: Nothing in ink on the calendar, just trying to do a lot of studio visits, and hopefully getting something pinned down soon. Yea, I just had a thing a couple weeks ago. It was a small group show that opened last Friday, or Friday before last. There was some great artists in that. Candace Williams, this guy Dapper Bruce Lafitte, greatest name ever. And Nikholas Planck was in it, he’s really great. I can’t remember who else, there was one other person but I can’t remember her name.

DK: Keep us posted if you do.

NS: Yea I will, definitely.

TW: Yea you heard it first, he’s available. Gallerists, beware.

NS: Yup. Take all comers.

TW: Alright, cool, well thanks again.

NS: Yea, my pleasure.

TW: And again, this is Open House, Debbi Kenote and myself, Til Will, and we are here with Nick Schutzenhofer, in lovely South Slope, Brooklyn.

7 episodes