But is it fascism?

Manage episode 431638879 series 3588922

For the last several years, both within and outside of the United States, there has been a lot of talk about fascism. The word, naturally enough, is always used in a derogatory manner, as not even the most fascist among contemporary individuals and movements actually want to be addressed that way. But what does it mean to be a fascist, exactly?

The word itself comes from the decision by Benito Mussolini, in 1919, to adopt the “fascio” as symbol of his new movement, which officially became a party two years later and seized power in Italy in 1922, capitulating only in 1943 near the end of the European campaigns of World War II.

The fascio (i.e., bundle) represented the power of the Tribunes of the Plebes in the ancient Roman Republic, derived from an even earlier tradition connected with the Etruscans. The same symbol was then reused during the French Revolution and the Italian Risorgimento (the war of national liberation) in order to represent the power of the people. It is therefore ironic, and somewhat shrewd, that Mussolini adopted it to epitomize the spirit of his autarchic system of government.

A common dictionary definition of fascism runs something like the following: “An authoritarian and nationalistic right-wing system of government and social organization.” My Apple dictionary helpfully adds: “The term Fascism was first used for the totalitarian right-wing nationalist regime of Mussolini in Italy (1922–43); the regimes of the Nazis in Germany and Franco in Spain were also Fascist. Fascism tends to include a belief in the supremacy of one national or ethnic group, a contempt for democracy, an insistence on obedience to a powerful leader, and a strong demagogic approach.” Now we are getting somewhere. So far, we have the following elements:

Authoritarianism

Nationalism

Right-wing ideology

Contempt for democracy

Demagogy

Single supreme leader

As the dictionary observes, Nazism and Franchism—together with similar regimes in other times and places, like the one set up by Pinochet in Chile—were all examples of fascism (many more are listed here). Why?

If we look again at the list above, we see that the very same characteristics—except for the rather unhelpful “right-wing ideology”—also mark dictatorial or totalitarian regimes that we usually associate with “the left,” for instance Stalin’s Soviet Union. Authoritarianism? Check. Nationalism? Check (despite pretenses to internationalism). Contempt for democracy? Check. Demagogy? Big check. Single supreme leader? Yup.

It begins to look line “fascism” is a synecdoche for different totalitarian or autocratic movements that emerged after the original Mussolinian fascism. In fact, Umberto Eco, in a classic essay entitled “Ur-Fascism,” suggests that the word is an example of what philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein referred to as family resemblance concepts. To deploy Eco’s own crystal clear explanation, consider the following sequences of letters:

abc

bcd

cde

def

The first and the second sequences are similar in that they share two letters (b and c). The second and the third sequences are also similar, sharing c and d. The same goes for the third and fourth sequences, which have d and e in common. However, the first and the fourth sequences have nothing in common. And yet, they are linked within the series by the process of shifting similarities. That’s what family resemblance is, according to Wittgenstein. As Eco puts it:

“Fascism became an all-purpose term because one can eliminate from a fascist regime one or more features, and it will still be recognizable as fascist.”

The Spanish dictator Francisco Franco was a fascist, but he was not an imperialist, unlike Mussolini and Hitler. Add paganism and polytheism—both alien to the original fascism—and you get Nazism. And so forth.

This flexibility, according to Eco, is the result of the fact that the first fascism was not really a coherent ideology at all, unlike some of its later instantiations. Mussolini’s movement had no specific essence, but was instead an hodgepodge of different philosophical and political positions, some of which were contradictory. Eco reminds us that it combined monarchy and revolution, a Royal Army and a personal militia for the Duce, privileges for the Catholic Church and an educational curriculum extolling violence, complete centralized control and a free market.

The Philosophy Garden is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Nazism and Stalinism, by contrast, were far more internally coherent, and possibly in part because of that so much more effectively lethal. Please note that this does not mean, as it is often claimed by some in modern Italy, that fascism was a “light” dictatorship characterized by a certain degree of openness and tolerance. The appearance of tolerance and the reduced level of lethality were the result of philosophical confusion, not of a more humane approach to autocracy.

I want to come back for a moment to the concept of a right-wing movement, as opposed to a left-wing one. Let’s again begin with the basic dictionary definitions.

Right-wing: “Political party or system that advocates for free enterprise and private ownership, and typically favors socially traditional ideas.”

Left-wing: “Political party or system that advocates for greater social and economic equality, and typically favors socially liberal ideas.”

Stalin most certainly did not favor “socially liberal ideas,” nor was his regime one that promoted social and economic equality, official rhetoric notwithstanding. It seems to me that while there certainly are right- and left-wing political parties (as well as other meaningful dimensions of political differences), those labels become meaningless when it comes to dictatorships and totalitarian regimes.

You may have noticed that I keep referring to dictatorship, or autocratic governments, as if they were distinguishable from totalitarian ones. That’s because they are, as superbly argued by Hanna Arendt in her classic book, The Origins of Totalitarianism. Indeed, one of the best ways to grasp the difference is to contrast Mussolini-style fascism with Hitler’s Nazism.

A totalitarian regime is one that attempts to subordinate every act of the individual and every aspect of society to a particular state-promoted ideology. Both Nazism and Stalinism were examples of totalitarianism. Fascism was not for the very reason Eco highlights in his essay: it lacked a coherent philosophy, so that there was nothing to totalize. Eco puts it bluntly:

“Mussolini did not have any philosophy: he had only rhetoric. He was a militant atheist at the beginning and later signed the Convention with the Church and welcomed the bishops who blessed the Fascist pennants.”

Neither Hitler nor Stalin did any such thing. Nor does North Korea’s dictator Kim Jong-un. By contrast, Vladimir Putin can be seen as a fascist in the style of Mussolini, not a totalitarian. Again, this is not meant as any sort of backhanded compliment, nor certainly as an endorsement of the actions of these people.

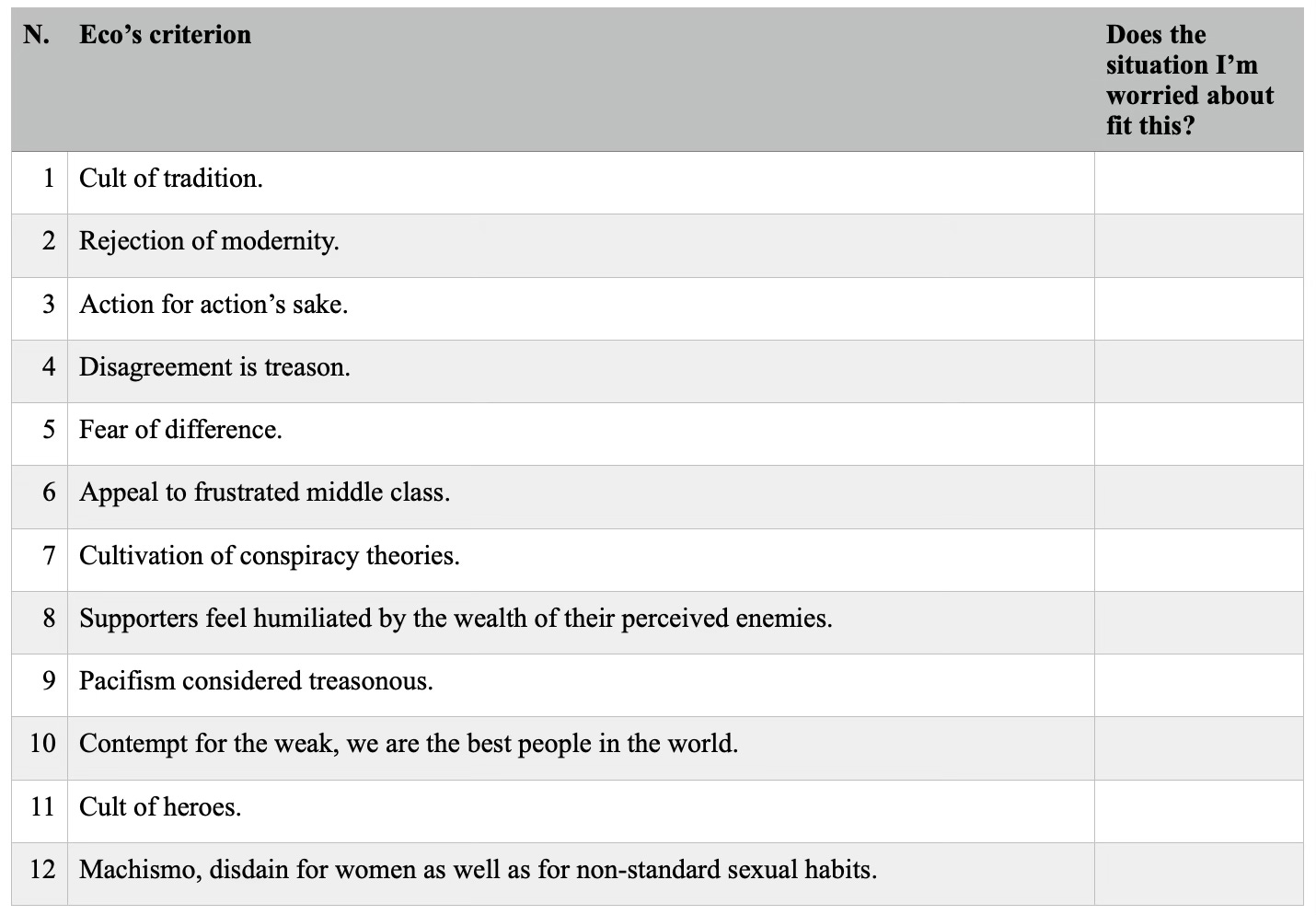

Eco concludes his famous essay on Ur-Fascism (i.e., the archetypal fascism) with a catalog of twelve points that we can use as a checklist to see whether a particular regime we may be concerned about is an instantiation of fascism. I’m presenting the checklist below for your practical use. There is no particular meaning to the sequence of criteria, it is simply the same one used by Eco.

Most of the entries are self-explanatory, but a few may benefit from a quick commentary. N. 2, for instance, rejection of modernity. This is not to be equated with rejection of technology. The Nazi were not Luddites. Rather, what is being spurned by fascists is the sort of modern ideals that emerged from the Enlightenment: the use of reason and science for the betterment of humankind. Fascism is fundamentally a cult of irrationality.

N. 3, action for action’s sake, is typical of anti-intellectualism, epitomized by the infamous saying “those who can’t do, teach.” When you do without thinking about what you are doing and why, action becomes destructive rather than constructive.

N. 5, fear of difference, means that the fascist’s ideal society is ethnically homogeneous, because anyone who looks different is perceived as a potential threat. Xenophobia is considered a virtue.

N. 8 concerns the notion that supporters of the movement and its Leader need to feel humiliated by the wealth of their perceived enemies, be they Jews—always a convenient target—or latte-drinking and electric-car driving “liberal elites.”

Finally, regarding n. 11, the cult of heroes, Eco writes:

“The Ur-Fascist hero is impatient to die. In his impatience, he more frequently sends other people to death.”

The rest, as I said, ought to be self-explanatory. So, what is all of the above good for? The next time you hear the word “fascism” being casually thrown around, consider whether it actually fits the situation, and make sure not to overuse it yourself, or it will gradually lose meaning. If you live in a place where there is a suspicion that a fascist government is being developed, or a potentially fascist party is surging at the elections, use Eco’s checklist to see how much you should really be worried, and how much you may need to get involved in order to forestall further undoing of the democracy you currently enjoy. Don’t forget: both Mussolini and Hitler initially got elected by perfectly legal and democratic means.

20 episodes