The universality of virtue ethics—I—Buddhism

Manage episode 430861489 series 3588922

Virtue ethics is one of the three major approaches to ethics developed within Western philosophy, the other two being Kantian-style deontology and Bentham and Miller-style utilitarianism. I think the latter two are good examples of wrong turns in philosophical inquiry, as they are both decidedly less useful (in my opinion) than virtue ethics.

Both deontology and utilitarianism seek to establish a universal, agent-independent criterion for the moral evaluation of human actions. In the case of Kantian deontology, an action is moral if it accords with the famous categorical imperative: “Act as if the maxims of your action were to become through your will a universal law of nature,” Kant says in his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.

In the case of utilitarianism, an action is moral if it increases the overall amount of happiness in the population: “By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever according to the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words to promote or to oppose that happiness” (Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation).

This is not the place to get into an in-depth discussion of why I think these two approaches are misguided. Suffices to say that I think ethics is better understood as pertinent to specific (not universal) situations and criteria for action, and—more importantly—as concerned with the growth of the individual, not with impersonal rules or quantities to be maximized, let alone with allegedly objective judgments of “moral” or “immoral.”

Interestingly, there is good empirical evidence that the concept of virtue is universal across human cultures, despite local variation in the list and definitions of the various virtues. It is therefore reasonable to ask whether virtue ethics itself, that is an approach to ethics concerned with the cultivation of character, has been developed outside of the Greco-Roman (and, later on, Christian) tradition. I am therefore beginning a series of three posts where I will examine three of the major Eastern philosophies—Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism—and see what some scholars who specialize in those fields have to say about their relationship to virtue ethics. I don’t have a firm opinion about whether the authors I will discuss are correct or not, but I hope the journey will be useful to readers interested in exploring the general notion that virtue ethics could turn out to be more of a cross-cultural concept than might at first appear.

<<>>

So let’s start with Buddhism, concerning which a pivotal essay for our purposes is “Virtue Ethics in Early Buddhism” by Damien Keown, published in Ethical Theory in Global Perspective, edited by Michael Hemmingsen (SUNY Press). Keown suggests that Buddhism can be usefully thought of as a form of virtue eudaimonism. He focuses on the period from the beginning of the philosophy in the 4th century BCE to the rise of Mahāyāna Buddhism shortly before the turn of the millennium. Much of his material belongs to the canon of the Theravāda school, the only early school that survives today.

According to Keown, Buddha, like Aristotle, teaches that happiness is the highest good and that virtue makes an important contribution to our wellbeing. Throughout his paper he uses the terms happiness, eudaimonia, nirvana, and wellbeing as near-synonyms, for reasons that will hopefully become increasingly clear.

The highest good in Buddhism is nirvāṇa, and both it and the rare Buddhist who achieves it are characterized by virtue. As is well known, a fundamental Buddhist doctrine is that of the four noble truths:

i) Suffering (dukkha) is a characteristic of human existence;

ii) Dukkha results from desire (taṇhā);

iii) Dukkha can be ended (nirodha) by attaining nirvāṇa;

iv) There is a path (magga) to nirvāṇa.

Keown says that one might be tempted to think of Buddhism as a sort of “negative utilitarianism,” given its emphasis on the alleviation of suffering. In that scenario virtue would be a means to an end, as in Epicureanism, which accordingly is not usually classified as a eudaimonic school. But in fact many passages in Buddhist literature suggest that pursuing prudential values (like the elimination of suffering) in the absence of virtue undermines the telos or ultimate goal of nirvāṇa.

Figs in Winter: New Stoicism and Beyond is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

While a superficial glance at the four noble truths may lead one to assume that the problem to solve for a Buddhist is suffering (first noble truth), the real issue is desire (second noble truth). Keown translates taṇhā as “ego-driven desire” or “craving.” Seen like this, and similar to the Greco-Roman approach, the problem at hand can be conceptualized as a type of emotional-cognitive disorder. It’s the pursuit of false values (vipallāsa) that leads one to the cycle of disappointment known as saṃsāra. Accordingly, says Keown, “nirvāṇa is known as ‘the extinction of the vices’ (kilesa-parinibbāna) and is defined as ‘the end of greed, hatred, and delusion’” (i.e., the three root vices).

Making progress toward nirvāṇa means to gradually replace the three root vices with the three root virtues of unselfishness (arāga), benevolence (adosa), and understanding (amoha). Those who achieve this become a kind of “saint” (arahant), a figure that could be construed as somewhat analogous to the Stoic sage. The path to nirvāṇa (fourth Nobel truth) is made of eight concepts and their respective practices: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation.

Keown comments that the eight-fold path can be understood as comprised of three areas of training (which remind me, to some extent, of the three disciplines of Epictetus): morality, meditation, and wisdom. Morality, which includes right speech, right action, and right livelihood, emphasizes self-cultivation and therefore corresponds to the first-person, agent-centered view of Greco-Roman virtue ethics. Meditation includes right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation. Finally, wisdom has to do with right view and right intention.

The three areas are seen by Keown as supporting each other, and he conceptualizes nirvāṇa as the confluence of the three areas of training. Again, perhaps this is a bit like how the three disciplines of Epictetus (desire, action, and assent) interact with each other and lead, when properly practiced, to sagehood (although Epictetus himself never actually mentions sages).

Of course, the Buddhist virtues do not coincide with the Aristotelian ones, at least in part because of diverging cultural conceptions of human well-being. Nevertheless, according to Aristotle the telos of human life has to have the following characteristics: it is desirable for its own sake, other things that one wants are ultimately for the sake of the telos, and it is never chosen for the sake of anything else. Nirvāṇa, suggests Keown, fits this list of desiderata, which makes a good overall case that nirvāṇa is in fact the Buddhist equivalent of eudaimonia.

The Greco-Romans themselves disagreed not about the general concept of eudaimonia, but rather about its content. Famously, for Aristotle eudaimonia consisted of virtue and some external goods, while for the Stoics and the Cynics virtue is both necessary and sufficient for a life worth living (in fact, for the Cynics externals positively get in the way, it’s all about virtue). In Buddhism as well, apparently, there have been historical disagreements on the nature of nirvāṇa, specifically whether it is primarily a moral, intellectual, or prudential good. Here is what the Buddha says:

“Wisdom (paññā) is purified by morality (sīla) and morality is purified by wisdom. Where one is, the other is, the moral man has wisdom and the wise man has morality, and the combination of morality and wisdom is called the highest thing in the world. Just as one hand washes the other, or one foot the other, so wisdom is purified by morality and this combination is called the highest thing in the world.” (Dīgha Nikāya, I.124, translated by Maurice Walshe)

According to Keown’s interpretation of the above passage, the Buddha defines “the highest thing in the world” (i.e., eudaimonia) as a combination of moral and epistemic (but, crucially, not prudential!) goods. He goes on to remark that Buddhist texts contain a number of Stoic-sounding passages denying the importance of externals. That said, and perhaps in a parallel with the difference between Stoics and Cynics, the Buddha himself agreed that self-mortification and the rejection of external goods—which he initially experimented with—is “a blistering way of practice.” Accordingly, the post-awakening Buddha is recognized to possess a number of worldly goods, including health, beauty, and longevity, thus perhaps beginning to sound very much like an Aristotelian!

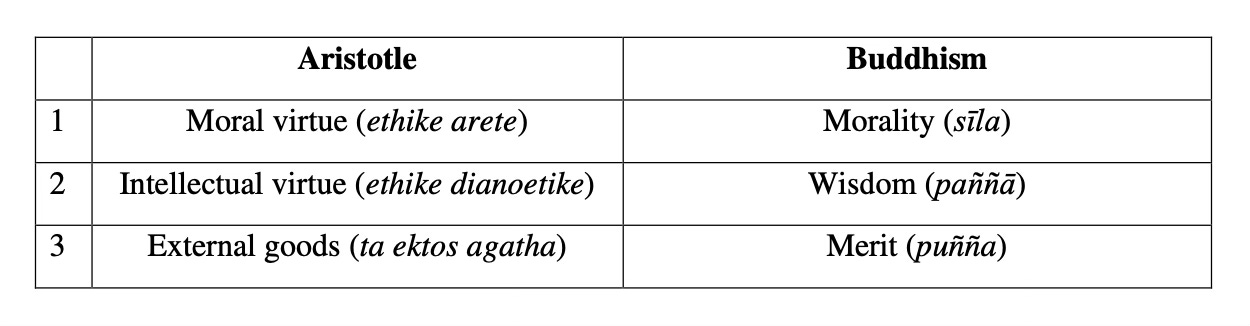

In a further parallel with Aristotle, the Buddhist notion is that virtue controls the proper use of external goods, which means that virtue itself is necessary but not sufficient for happiness. However, again as in the case of Greco-Roman eudaimonism, the pursuit of prudential goods as an end is a mistake which leads to saṃsāra rather than nirvāṇa. Here is a table summarizing the components of wellbeing according to Aristotelianism and Buddhism:

At the end of the essay, Keown does recognize the existence of a number of differences between Buddhism and the Greco-Roman eudaimonic traditions, particularly when it comes to metaphysics. But he proposes, in agreement with another modern Buddhist scholar, Owen Flanagan, that nirvāṇa and eudaimonia belong to the broad family of “natural teleologies.” Keown concludes:

“If the four noble truths are understood in the way suggested in this essay, the motivation to attain nirvāṇa is not the avoidance of suffering but the pursuit of excellence. In Buddhism, this excellence extends, as it does for Aristotle, to social engagement, an engagement epitomized in the Buddha’s decision to teach the Dhamma [i.e., natural law] and the heroic mission of the bodhisattva to save sentient beings.”

[Next: Confucianism as virtue ethics?]

20 episodes